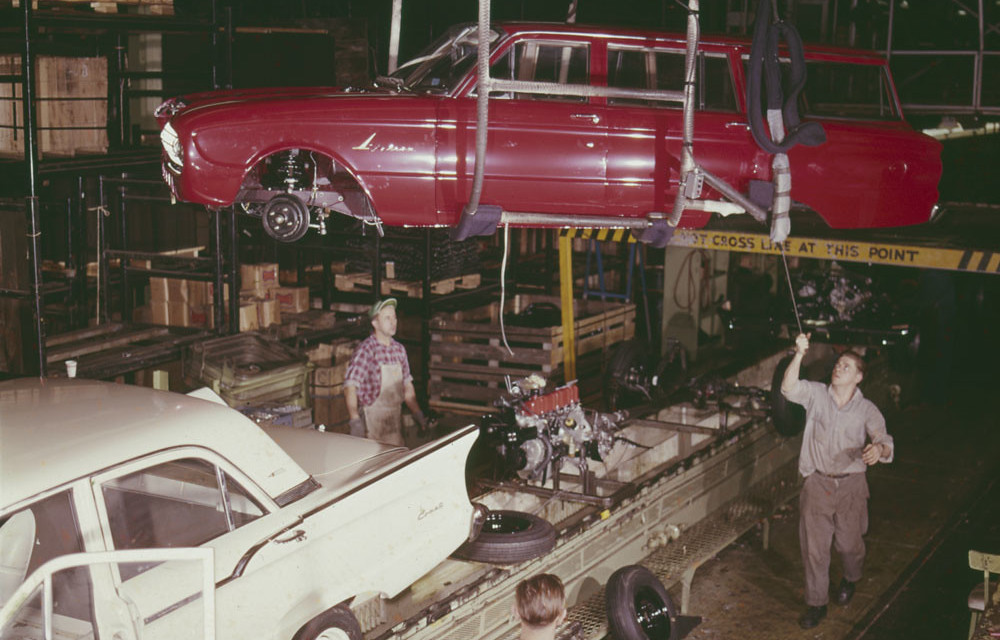

At 2 pm on Dec. 18 the last truck rolled off the line at the General Motors assembly plant in Oshawa. The closure means the loss of 2,300 jobs. A clutch of 300 workers will stay on at the plant stamping panels and doors, and the site is being converted for testing autonomous vehicles.

The demise of the assembly plant caps a long, dark decade for manufacturing in Canada. Will the 2020s be better?

Well, if the trend holds the coming year will see the industry finally recover to its pre-Great Recession high of 15 years ago. But that’s only when measured by GDP. In terms of manufacturing jobs it would be nice just to see employment recover to the level it was at before the recession in 1974.

The reality is output from factories and the number of workers in those factories have been moving in different directions for decades. That’s because technology has enabled manufacturers to do much more with fewer people.

The chart below puts that in focus. In 1961, it took 30 workers to produce $1 million of manufacturing output in Canada. Today, that same level of factory activity can be achieved with just eight workers.

The inspiration for the chart came from this 2016 Brookings piece explaining why Donald Trump’s promise to bring factories back to U.S. shores wouldn’t result in a resurgence of factory jobs, which it hasn’t.

But as the above chart shows, something is obviously missing from this post-recession period that’s exacerbated the jobs-output disconnect. Even if the long run trend in manufacturing jobs has been more or less flat for 50 years, there were still job gains during periods when output was expanding and new highs were reached. Not this time.

From 2004, when manufacturing employment peaked, to 2009 when the 2008/09 recession ended and the recovery began, factories shed 610,000 jobs, Statcan’s monthly employment data show. Since then not a single net new manufacturing job has been created for Canada as a whole. Quite the opposite — in November there were 41,000 fewer manufacturing jobs than in November 2009.

One critical ingredient has been missing over this time: private investment in things like machinery and equipment, and intellectual property products. Here’s the same chart, only now with private investment in manufacturing overlaid.

Whereas private investment once led the sector higher, over the past two decades stagnant or falling levels of investment have acted as an anchor weighing it down. As much as technology has allowed manufacturers to get by with fewer workers, underinvestment in capital, machinery and equipment is taking its toll in the form of lower productivity and that’s restraining the ability of manufacturers to expand production capacity. And so you end up with anemic growth in output and no new jobs.

Can these trends be reversed? There have been signs of a pick-up in business investment. In the third quarter capital spending rose at the fastest quarter-over-quarter pace since 2017, but it’s unclear how long that will be maintained. And while it’s true that low-cost competition from other countries means a huge number of those manufacturing jobs lost since the early 2000s are never coming back, without significant investment Canada’s manufacturing output is almost certain to remain feeble and job growth nonexistent in the decade to come.